It takes a good man to fly the new P-51, world's fastest, longest-range fighter. Meet the riders of the Mustang.

FROM A MUSTANG BASE IN ENGLAND.

YOU can't say that Howard put the new Mustang on the map, because the P-51 did that for itself, with a big bang, by escorting the daylight Fortress raids deeper and deeper into Germany.

When they had enough Mustangs the bombers raided Berlin, and did it day after day. Probably that simple statement means more than to say it is the fastest airplane in the world.

Or to say that the Mustang is the highest flying, lowest-flying, longest-range fighter we have among all the superlative aircraft going out to strike the enemy.

New Mustangs are now delivered with their silvery aluminum bodies unpainted. The omission of paint results in a reduction of weight and drag that adds 10 miles per hour to their speed - one of many factors that make them the fastest and longest-range fighters in the world. The speed gain offsets the loss of camouflage.

Or that it takes a very tough man to keep up with the endurance and dependability of this light, fast-accelerating, maneuverable fighter, with its Packard-built Rolls-Royce Merlin engine. For the Mustang doesn't merely fly 500 miles into Germany, fight over the target for an hour and a half, shooting down four enemies for every loss, and then come home. It does this day after day after day, with hardly a bit of tinkering to be done on the ground.

All these things are true of the Mustang, and outstanding in themselves. But it was Howard's exploit that first really dramatized the arrival of this new fighter in the European Theater. Howard's few seconds of heroism were the bright spot in the black day of January 11, 1944, when 60 Fortresses went down in the raid on Oschersleben. So in telling about this wonder aircraft of 1944, it is natural to start with Howard and the incident which one grateful Fortress man described as "one lone American taking on the entire Luftwaffe." Singlehanded, he had fought with more than 30 German planes.

After all, if it hadn't been for the qualities of his plane "Ding Hao" (which is Chinese for "O.K."), Howard could never have done it.

Part II

Col. James H. Howard was a member of the Ninth Air Force fighter group which was the first outfit to be equipped with the new, improved Mustang. Originally he was a squadron leader. He succeeded to the command of Col. Kenneth Martin, who went down in a head-on collision with an ME-410 during a raid on Frankfurt. Howard is the only American who rates as an ace against both the Japs and the Germans. He is no glamor boy, but a seasoned, professional flyer, 30 years old.

Howard got his flight training as a naval air cadet at Pensacola in 1937, then served on the aircraft carriers Lexington, Wasp, and Enterprise. He wasn't any too satisfied in the Navy, foreseeing himself years later still flying the wing of some young officer from Annapolis. So in 1941 he resigned his commission and joined up with Chennault's Flying Tigers, the American Volunteer Group, to fight in China. Howard was born and brought up in China, son of an American doctor in Peking, but he can't recall that his volunteering had much to do with helping the Chinese. He wanted to get ahead as a fighter pilot. He wanted to participate in the development of new fighter tactics.

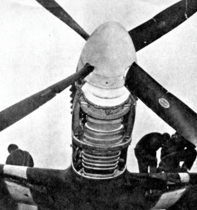

Another swastika is added to Howard's scalp rack. The six rising suns stand for Nips he brought down while he was with Chennault's Flying Tigers in China. Curiously, the American ace was born in China. His plane's name, "Ding Hao", means "O.K." in Chinese. He has also flown P38's, 39's and 40's.

He got his chance at the tactics. Around the officers' mess table in Burma he found a lot of young flyers hotly debating various ideas of how to fight in the air. Then these lads went out against the Jape to try the ideas, most of which turned out to be pretty poor. But out of these experiments over China came the two-by-two tactics used by American fighters today. Howard says the two-by-two idea originally came from the Germans, and its importance can be exaggerated. He says the important thing is to be willing and eager to try out new ideas. With the rest of the AVG, Howard tried out ideas on 56 combat missions. He shot down a half dozen Japs before coming to the ETO.

The opportunity to try new ideas came again to Howard when he was assigned to Mustangs. Up until then, he had flown Navy fighters, P-40's, Lightings, and P-39's. On December 1, 1943, in England, his group got the first shipment of Mustangs and set out over Europe to find out how good they were. For a month they felt their way. Then in January they started going, not to town, but to one German city after another.

The long range of the Mustang made possible a new development in the technique of escorting heavy bombers. Up to now the bomber formations had proceeded to the target under protection of successive groups of Thunderbolts, each of which flew with the procession for a while (either on penetration or withdrawal) and then retired when its gasoline ran low. Now the Mustangs, because of their long range, took over the sector above the target. Owing to their small numbers at first, the Mustangs would not stay with any one combat wing of bombers; they undertook to give "area support," staying over the target area for as long as an hour and a half, while as many as 10 combat wings of bombers came in, made their runs in the danger zone over the target, and departed.

Little friend and big friend: Fighters and bombers seldom meet except in the flak-filled air above enemy territory, since they operate from different bases. Here, however, a P-51 is shown with a Fortress that made an emergency landing at a Mustang base after having been pretty badly shot up with rocket shells.

The raid on Oschersleben on January 11 was one of the deepest yet attempted, and the Mustangs were to give target support beyond range of the Thunderbolts. The Mustang group, flying under Howard's command, made its rendezvous with two boxes (combat wings of 54 each) of bombers right on the dot.

But then, over the RT, came bad, startling news. A third box of bombers had got ahead, out of sight. And right now the Messerschmitts and the FW's were swarming in on it, blasting it unmercifully. Leaving two squadrons to protect the two boxes of bombers (which, as it turned out, were not attacked at all), Howard took his own squadron to the rescue of the third combat wing, which was unprotected.

The sky was alive with German fighters when they caught up. The Mustangs struck, and in the melee Howard's flight lost him. He had to fight on alone. At least he says he had to, quoting the old Chinese proverb: "He who rides the tiger cannot dismount."

After it was all over, flying back home with the stick in one hand and a pencil in the other, Howard jotted down notes on his knee pad, trying to disentangle the events of the last few minutes, when he had been alone among the German swarm. Here is what he wrote when he got home:

"When I regained bomber altitude, I discovered I was alone and in the vicinity of the forward boxes of bombers. It was here I spent approximately a half hour, chasing and scaring away attacking e/a (enemy aircraft). Each time I would climb back up to bomber level only to find another e/a tooling up for an attack. I was quite busy in a constant merry-go-round of climbing and diving on attackers, sometimes not firing my guns but presenting a good enough bluff for them to break off and dive away..."

Now the first principle of today's fighter tactics (learned from the Flying Tigers after their experiments in China) is that when a fighter makes a bounce, he wants a wing man to protect him. But Howard was trying something new.

The excitement started when the Fortresses got home, the battered remnants of those which had stood the brunt of the attack. They had not only taken a terrific shellacking; they had had grandstand seats for an amazing one-man flying circus. They insisted on a search of combat reports to find out who this flyer was. Howard's report seemed to fill the bill.

The commander of the battered combat wing wrote Howard the following:

"Your unprecedented action in flying your P-51 alone and unaided into a swarm of German fighter planes, estimated between 30 and 40, in an effort to protect our Fortresses in the target area, is a feat deserving of the highest commendation..."

This went on for some hundreds of words. Howard himself put in a matter-of-fact claim of two enemies destroyed, two probables, and one damaged. The combat assessment board, after skeptically reviewing the available facts, couldn't quite swallow that one. They credited him with three outright kills.