Part III

The Mustang is a product of North American Aviation, Inc., but to a great extent we owe it to the British. The first military plane to be developed in America during the present war, it was first manufactured in November 1941, in response to a request from the RAF for a fast, low-flying fighter, to be used by the Army Co-operation Command. Driven by a 1,150-horsepower Allison engine and designed for extremely low flying, the original Mustang soon made a name for itself as a rhubarb plane, busting trains with four 20-mm cannon. Americans didn't go for it especially, although they did take it in a dive-bombing version known as the A-36 Invader, which did fine service in the African and Sicilian campaigns.

The British liked the Mustang tremendously, and it was their idea that it should be fitted with the Rolls-Royce engine, which the British (not without reason) consider the outstanding mechanical phenomenon of our time.

Thus it was that the new Mustang was fitted with the Packard version of the Merlin engine in the latest type-with a two-stage supercharger making it the equal of any aircraft in high-altitude performance. This engine has a confessed horsepower rating of 1,520, and gives the plane maximum effectiveness three miles higher than any earlier P-51. But it is still good close to the ground, as evidenced by the sudden emergence of Lt. (now Captain) Don S. Gentile as a leading ETO ace with 27 planes destroyed, a half dozen of them on the ground.

The P-51 is 32 feet three inches long, 13 feet eight inches high, and weighs 9,000 pounds. It has a wing span of 37 feet and a tail span of 11 feet 10 inches. Its wing area is 233 square feet. To handle its tremendous power it has a four-blade propeller, 11 feet two inches in diameter.

The new Mustang soon demonstrated its ability to outclimb, outrange, and outmaneuver any German aircraft. In three consecutive raids the Mustangs shot down 30 Germans without a loss. Jerry does not like to tangle with them.

Part IV

Recently North American was permitted to announce that the Mustang, with a published speed of 425 miles an hour, is the fastest aircraft on earth-capturing this rating from the twin-engined British Mosquito.

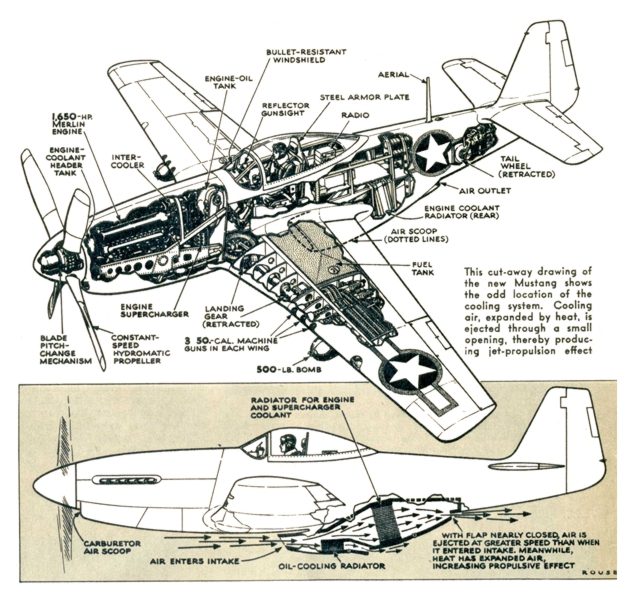

Various factors in the new version contribute to this speed. One of these is the exhaust ejectors at the side of the engine cowling, which are worth 200 or more horsepower in propulsive effect. Even more important is the redesigned cooling system, which gives the airplane its characteristically fat belly.

This radiator cowling is set far back, so that the entire front end of the airplane is very clean, striking undisturbed air. But especially important is the fact that this system is so designed that air passing over the radiator and expanded by heat is ejected through a much smaller flap opening at the rear. This use of the principle of jet propulsion recovers 80 percent of the power lost through drag of the cooling system.

Heart of the new Mustang is the Rolls-Royce Merlin engine as built in Detroit by the Packard Motor Company. Souped up to a vast increase over the power of the Merlin in the Battle of Britian, it has an announced horsepower of 1,520 and its two-stage supercharger can maintain full power well above 30,000 feet. One P-51 Merlin pulled "emergency" manifold pressure for 40 minutes without harm.

As for the engine, which also has a lot to do with it, let me tell you the story of one of Howard's flyers:

Lt. Clayton K. Gross, of Spokane, Wash., has been shot at plenty, which is why his Mustang is called "Live Bait." But worst of all was the day coming back from Frankfurt, when suddenly his wingman was gone and there behind him were four Focke-Wulf 190's roaring in to complete the kill.

Gross went right through the gate into the kitchen. He did a split S to the deck and stayed there, with his throttle on the fire wall.

He soon lost his pursuers. But the next 40 minutes - tearing through telephone wires, clipping the tops of trees, skimming housetops, dodging windmills at more than 400 miles an hour-were the loneliest of his life.

The trip was eventful. At one point Gross was suddenly enveloped in a grinding, blinding flash and shower of sparks. His Mustang had ploughed through a set of high-tension wires. But it never faltered. Once he ran into six Focke-Wulfs and thanked fortune their wheels were down for landing.

When he had gone into the kitchen – that is, into a turning dive with everything on – he had pushed the throttle as far as it would go, past the gate, the maximum military power. You are permitted to go to a "war emergency" manifold pressure for five minutes. But as Gross came in to circle his home airdrome, he realized he had been against the fire wall all the way. This Packard-built Rolls-Royce Merlin engine had been pulling "war emergency" for all of 40 minutes. And she was still doing it like a sweetheart.

This Mustang had come back with its air scoop, under the belly, half torn off, with a yard length of 8/8-inch high-tension cable embedded in the radiator. But what really made the ground crew bug-eyed was the engine and what it had stood.

Lt. John Konopka, who mothers the Mustangs with passionate zeal, drained the oil and strained it, hunting for metal chips. He had the crew tear the engine down and reassemble it, gave it an hour's slow flying, drained and strained the oil again. Not a chip or sign of wear. Everything perfect.

"Boy!" said Konopka. "That Merlin may be English, but it sure is some engine!".