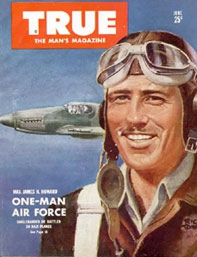

Maj. James H. Howard, fighter pilot of the 9th Air Force. The Oeschersleben mission on 11 January, 1944

Here in an up-to-date long-range Fighter Escort base they have just unmasked a "one-man air force," a secret weapon which has chased the Luftwaffe at odds of thirty to one, a typical American pilot and a sensational American airplane. They are Maj. James H. Howard, six feet, two inches of thin-hipped, broad-shouldered, quick-thinking pilot skill and the P-51B airplane, the Mustang.

To be like him you need a "hot" airplane and a cool pulse. You must be at home in the highest altitudes and yet "keep your feet on the ground."

This combination, along with others nearly like it, are setting new world records almost daily as they escort Flying Fortresses and Liberator bombers from Britain into Germany. They have made trips of over 450 miles to the target, and at times fought in the target area for an hour and then returned. This is roughly equal to taking off from Portland, Oregon flying to San Francisco, fighting, and then flying back.

In the thought that you might want to get a close-up of the hero of this base, I journeyed to Major Howard's group headquarters and spent four days with him and his fellow fighters of the 9th Air Force. I brought back the major's own description of his sensational aerial combat of January 11, when, protecting bombers on a raid over the Oeschersleben Halberstadt Brunswick area, he was seen to take on twenty to thirty two-engine Messerschmitt 110's, eight or more sleek, single-engine fighters and a few odd Dorniers and night fighters. Bomber crews made out reports that they saw six of the enemy go down.

Major Howard’s estimate: two kills, two probables, two damaged. And I learned that if he is the perfect pattern for an American ace, and the experts tell me you couldn't find a better, there are some rules to follow. To be like him you need a "hot" airplane and a cool pulse. You must be at home in the highest altitudes and yet "keep your feet on the ground." To follow in his slipstream you must be a very rugged individualist indeed, and practice your credo, you must base your tactics on teamwork. Contradictory? Perhaps. But well, so is this Maj. James Howell Howard. But he adds up to a colorful story-book character.

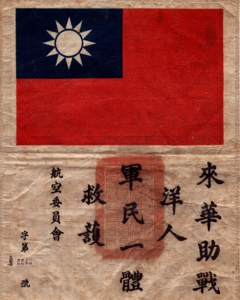

To begin with, though he seems so typically American that you swear you've seen him somewhere in the States, he was born thirty years ago in Canton, China and has spent almost half his life abroad. Though he's got so sort of a record for a day's shooting in this entire Theater of Operations, he started out as a Navy pilot and went from that to a Squadron Leader's command in the famous Flying Tigers of Burma. He was deputy leader there under famous "Scarsdale Jack" Newkirk and took over after Newkirk was killed. He is credited with six and a third Jap planes, and thus he is a double-header ace, an ambidextrous big-leaguer of the skies.

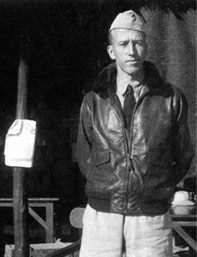

Assigned to the AVG "Panda Bear" 2nd Sqdn, Howard in his P-40B fighter at Toungoo, Burma, Dec. 1941.

He is as plainly American as the jeep. And like it he is durable, reliable, speedy and possessed of a four-wheel driving mechanism. He uses the "drive" in getting routine jobs done on the ground. In the air he is like a different person entirely. He is a great air "general," a fine strategist and a matchless fighter. He smiles almost constantly up there, his fellow pilots say, and when he lands with a grin and comes in to report you may be sure Goering has been whittled down some more.

He eats sweets almost constantly, doesn't care much for pin-up girls, isn't superstitious, likes the movies but isn't particular about the stars and says he hasn't a regular girl friend. His parents, Dr. and Mrs. Harvey J. Howard, of 20 Crestwood Drive, St. Louis, Mo., used to tell him his branch of the Howard family was related to the Howards, headed here in England by the Duke of Norfolk. So at a recent public function Major Howard asked Queen Elizabeth if the Duke were around. He wasn't, but at the Queen's suggestion wrote Jim Howard a letter. Now they're going to get together for a chat.

The biography of this Lancelot - with 1,500-horsepower can best be told through the nicknames he's earned. "Jimmy" brought him running back in the days when his father was a medical missionary in China and was captured by the bandits there, later to write a book about it. "Slim," he was called when he went to boarding school at Haverford School, Haverford, Pa., and later for three years at John Burroughs High School, St. Louis, and at Pomona College where he prepared for the study of medicine, entering as freshman when Bob Taylor was a senior. He used to play a bit of tennis with the movie star who then had to spell out his name Spangler Arlington Brugh.

The next nickname he earned was that of the "Busy Beaver." But that didn't come until after he had taken up flying in the Navy short course then offered - and completed it successfully to his surprise-flown three years from such famous decks as the Lexington, the Wasp and the Enterprise. (He went into aviation because he'd read books on Lindbergh and the great German ace, Baron von Richtofen, and because it seemed like a good opportunity to learn at Navy expense.).

Now it seems that a "busy beaver" is a fellow who is just so much in love with activity that he volunteers for whatever comes along. Which is only a partial explanation of why he volunteered at the first opportunity to join the American Volunteer Group being set up to fight the Japs under the direction of General Claire Chennault. Other reasons were that he knew the Japs had to be fought one day, the peace-time Navy had too many anchors and not all of them without gold braid, and he had reason to respect the Chinese people-he'd lived among them many years.

Over here a job like that is called "rhubarbing," because you get down so low you almost do the weeding.

He was stationed at Mingaladon Airdrome and between Dec. 30, 1941 and Feb. 8, 1942 he went on fifty-three missions. He made those old Tomahawks lift many a "scalp." One of his favorite stunts was shooting up Jap airdromes. Over here a job like that is called "rhubarbing," because you get down so low you almost do the weeding. Over there they would listen by the hour to Chennault explaining the Japanese "bible," or book of instructions, they would mark the whole thing down as an exercise, then go out and rev up the battered P-40's and make history with a steady, almost untutored hand. Jim Howard thinks there's been a bit of overwriting done about their "tactics." The two-man system of fighting wasn't devised there, he told me. They trained hard, studied hard and did what they were told, for the most part, but the tune they made the Zeros dance to was played by ear.

Take the time Newkirk, "Tex" Hill and Howard went over and shot up the airfield at Tak. They knew that the Japs had built grandstands for themselves and some Thailand officials whom they hoped to impress with their aerial prowess, and that at a certain hour they could be caught with their kimonos undone. Newkirk was leading, then came Howard, then Hill. Jack was to engage whatever Jap fighters were around, Jim was to strafe planes on the ground, Hill was to help out in either department and, as well, strafe Jap soldiers.

"We swooped down on them and they scattered like ants," Major Howard recalls. "They were losing face every second. Jap soldiers on the runways fired their rifles at us and then were mowed down. Newkirk took on a Zero which came swooping in while I had my eyes glued on a row of airplanes neatly parked along the far strip.

A Brewster F2A, the U.S. Navy's first monoplane shipboard fighter. The type indentified by Howard on the 3 January 1942 mission to strafe Tak airfield.

"I saw they were American-built Brewsters and knew immediately that they were ships which had fallen into Jap hands when they invaded Thailand. I determined they'd never get to use those aircraft against us. I darted over there and let the tracers flow. Incendiaries blew up tanks and set them all on fire, but I wasn't satisfied. I ran back and forth over those ships tossing riddling steel into them.

"By George, I was so busy doing that I didn't see a fast Jap fighter who was so close to my tail he was practically getting into the act! But, "Tex" Hill shot him down. As we flew home he told me about it. I didn't believe him. But when I put my hands on those bullet holes later "Tex" said, reprovingly: "Those didn't come from moths, you know."

"I saw they were American-built Brewsters and knew immediately that they were ships which had fallen into Jap hands when they invaded Thailand. I determined they'd never get to use those aircraft against us. I darted over there and let the tracers flow. Incendiaries blew up tanks and set them all on fire, but I wasn't satisfied. I ran back and forth over those ships tossing riddling steel into them.

Squadron Leader Howard flew long, solitary reconnaissance missions. He escorted bombers. He went on fighter sweeps. He helped organize physical training classes around the airdrome. He rode a bicycle about and kept in trim. Whenever new airplanes would arrive at Rangoon be took his turn going down, seeing the sights, and bringing the new planes back.

He was aid to the Chinese general commanding the air force and he helped plan the layout for the airport at Chungking. He was sorry to see the AVG's disbanded because they had much of the stuff which he so admires: guts and adaptability. By that time the United States was in the war. It didn't seem right for the Tigers to get a bounty of $500 or so for each Jap shot down when other Americans were happy to do it at G. I. rates. Back in the United States Jim Howard enlisted in the air force and soon was a major. He was assigned to a squadron which seemed hexed with adversity of the grimmer sort. It had lost two squadron leaders, both by flying accidents, and was building up its legends-all negative.